Article

Winter | 2025

Writing Reports for Conviction

Daphne Tarver, Donna Fraser, Tiffany Griffin

Winter | 2025

This article is the third of a three-part series. The first installment discussed the importance of the police report, impact of poor coordination between law enforcement agencies and prosecutors, and barriers impacting officer’s ability to compose detailed reports. The second installment provided a pathway for law enforcement leaders and prosecutors to work together to identify issues with investigative narratives and improve them. This final installment provides an overview of the details that must be included in a report to obtain a conviction. “The information provided in police reports is paramount for the successful prosecution of criminal cases and the conviction of offenders.“1 When reports do not have the requisite information to prosecute the case, follow-up investigations must be conducted, or there is an increased likelihood the case will be pled down to a lesser offense or dismissed.

"The police report is by far the most important piece of evidence in every criminal case. "

No one has ever pursued a career in law enforcement with the goal of writing reports. Despite that, preparing well-constructed, accurate, and comprehensive reports is essential for attaining convictions. Those officers who do not develop this requisite skill will never be effective in serving their community.

Every action an officer takes is a reflection on them. From the moment an officer is dispatched to a call, they have a duty to support what, why, and how the officer took an individual’s constitutional right of freedom. Preparing quality reports is a mindset that must permeate every level of a law enforcement agency. The mindset to document their observations and actions, mindset to collect evidence, mindset to effect lawful arrests and convictions. This requires they justify every action taken by documenting them in the investigative narrative. When composing this narrative, there are several steps that must be articulated.

Standing

The first step is to describe the officer’s legal ‘standing’ to be in a location within their jurisdiction and observe a violation of the law.

“On Saturday, September 21, 2024, at 1832 hours I, Officer John Smith, was dispatched to a domestic violence call at 123 Johnston Drive, Anytown, Georgia.”

“On Saturday, September 21, 2024, at 0130 hours, I, Officer John Smith, was on routine patrol driving eastbound in 400 block of Main Street, in Anytown, Georgia when I observed a blue 2021 Hyundai Sonata, with Georgia tag ABC123 travelling ahead of me with two flat tires on the passenger side of the car.”

Reasonable Suspicion

The second step is to describe observations that led the officer to have ‘reasonable suspicion’ a crime has occurred or is in the process of being committed.

With the domestic violence call, the officer would describe, When I arrived at 123 Johnston Drive, I parked one house east of the incident location. As I walked toward the front door, I heard two persons inside the house talking loudly. A male, later identified as Carl Smith, was saying, “You are going to quit spending my money on furniture and clothes unless I tell you.” I also heard a female, later identified as Mary Smith, who was crying and saying “Okay, okay, please don’t hit me anymore.”

In the case of the officer following a car with two flat tires, they may elaborate on their observations by indicating, “In my eight years as a police officer, I have found it uncommon to see a car driving with two flat tires. As I followed the driver, who was driving 35 mph, they never slowed down or turned on their emergency flashers. It was 0130 hours. This is a time when the local bars begin closing. Because of this, I suspected the driver may be impaired, struck a curb, and damaged the tires or wheels.”

It should also include a description of how the vehicle was being driven, for example did they suddenly braek, did they cross the center line or fog line? How many times within an approximate distance?

Probable Cause

The next step is to articulate “probable cause” to make an arrest for a criminal offense by describing the facts and circumstances that would lead a reasonable person to believe a crime has occurred. To successfully accomplish this requires the officer to articulate the facts substantiating the ‘elements of the crime’ with the family violence call.

Once the officers were inside and announced they received a 911 call regarding a disturbance, what were their responses? Did the officer observe any marks, bruises, or injuries? Who was the primary aggressor? How many times have officers been dispatched to the location for similar calls? Were there any children present? Was there any property damage? Did the officer(s) talk with the suspect and victim separately? What did the alleged victim say? What did the alleged suspect say? Did the suspect make any ‘threshold statements’ (i.e., “I lost my temper and hit her. I should not have done that.”). Were the two in a relationship (i.e., live together, married)? Describe the alleged victim’s behavior (i.e., crying, covering part of their face or other injuries). Were there any other witnesses? If so, who were they, including contact information and whether they were interviewed and provided statements.

With the suspected DUI driver, the officer should describe activating their emergency lights, how far before the suspect recognized the officer was behind them. When the officer approached the car, what did they observe? Was there an odor of alcoholic beverage in the car or on the driver’s breath? Was there an open alcoholic beverage in the car? What did the driver say when asked where they were coming from and going? When the officer told the driver they stopped them because they were driving with two flat tires, how did they respond? What physical behaviors did the officer observe, unsteady on their feet, glassy eyes, swaying? Did the officer conduct field sobriety tests? If so, which ones and include a detailed description of the individual’s performance. When and where did the officer read implied consent warnings to the driver? Was the arrest recorded on a body worn or in-car camera. Include a reference to any video recordings.

Beyond a Reasonable Doubt

The next step is critical to achieving a conviction. This requires there be sufficient evidence to prove beyond a reasonable doubt the individual committed the offense in which they were charged. Beyond a Reasonable Doubt is not “beyond all doubt”. Rather, it is the culmination of well-documented facts and evidence that rules out any reasonable possibility someone else committed the crime. To meet this threshold, there should be a systematic follow-up on all aspects that are developed. If anything is missing, ignored, or disregarded; “reasonable doubt“exists. If this occurs, the time spent on the arrest was a waste.

Evidence Collection

Properly photograph, collect, package, seal, and label any evidence that was collected. Once this is accomplished, complete the evidence forms to establish the chain of command. Copies should be included with the report and the packaged evidence when it is stored in the department’s temporary evidence storage lockers.

Miranda Warnings

Was the individual read their Miranda Warnings? If so, clarify when and by whom. Did the person agree to speak with the officer? Did the suspect sign a Miranda warning form?

Oral/Written Statements

If the person agrees to talk with the officer, include a summary of their statement. While oral statements are good, having individuals to write a statement is much better. If the interview was recorded include a reference for the recording.

Witnesses

Identify witnesses or other persons who were present to include their names, addresses, and contact information. Did the witnesses make comments to the officers? Did they give a statement? Were these statements written, recorded on body worn cameras (BWC), or captured using some other format? Were there witnesses who observed the offense who were not present when the officer(s) arrived? Were these persons located and interviewed?

Photographs

Do not rely on BWC images! The use of digital cameras enables officers to effectively capture images of the crime scene at little cost. Each of the photographs should be documented in a photographic log that includes a description and the location.

Collect multiple images of the crime scene and specific items that progress from the overall crime scene to close-up images. Collect detailed images of evidence that is to be collected for examination (i.e., weapons, fingerprints,) with and without scales.2

In some cases, it may be necessary to meet with the victim to photograph injuries that become more visible in the next day or so. Sometimes, the use of a black light or alternative light source can better identify additional evidence of previous assaults.

Physical Evidence

In a period in which CSI programs and investigative television programs are continually broadcasted, the public assumes officers collect evidence in every case. For example, did the officer attempt to lift fingerprints, did they photograph damage, victim’s wounds, collect evidence that possibly contains DNA. If they do not attempt to collect it or did attempt but did not document their action, it may be viewed as though the officer did not have the evidence needed to support the case.

To illustrate how the failure to attempt to collect evidence can impact the outcome of a case is an exchange that occurred between a defense attorney and the detective assigned to the case. During cross examination, a detective was asked if they attempted to lift fingerprints at a scene. The detective responded no. When asked why they did not attempt to lift prints, the detective responded,

“90 percent of the time we try to identify and lift prints, we do not attain any”. The defense then asked, “Isn’t it true that a 100 percent of the time you do not attempt to lift prints you don’t get anything?” The officer responded “yes”. The defense attorney then noted, “Isn’t it true that if you attempted to lift prints, you could have possibly collected evidence of who may have actually committed this burglary and cleared my client?” This statement can go far in demonstrating reasonable doubt.

When investigating a criminal offense and preparing a report, officers should assume the case will result in a bench or jury trial. During this process, they must anticipate every question the defense may ask. This requires every potential witness be interviewed, and all evidence be collected and analyzed.

Occasionally, officers experience confirmation bias. When this occurs the officer only considers information and evidence that supports charging one person and do not follow-up on information that suggests another person may have committed the offense. Confirmation bias can happen anywhere to anyone. When it is obvious who the perpetrator is, “why pull out all the stops”? Calls for service are holding, and they cannot spend all day at one incident. A trial might not even happen, they probably will not even fight the charges. Evidence lost to the “theory” of what happened or not finding evidence relevant because it did not fit into the “narrative” is an unnecessary trap defense lawyers will capitalize on every single time, often leaving officers’ reputations damaged and criminals acquitted.

Officers have a duty to consider any evidence that can exonerate a person and only arrest the person who committed the offense. To accomplish this, any evidence that could exonerate a suspect must be examined and included in the report along with a description of the actions taken to confirm its validity.

Evidence Forms

Properly identify, collect, package, seal, and label any evidence that was collected. Include “Submission for Analysis” forms to ensure items are sent to the crime lab. Once this is completed, each of the steps taken must be articulated in the investigative narrative.

Formatting

When determining how reports are to be formatted, there is no ‘one best way’. As discussed in previous installments of this series, it is important to work with prosecutors to prepare a common format to address the needs of the department and the prosecutor. Generally, when composing the report, the narrative should be written in chronological format using first person tense to describe the actions of the reporting officer. Actions of other officers who may have been at the incident location, conducted some investigative processes, and made observations should be documented with supplemental reports.

Other formatting issues include common topic headings, paragraph breaks, and use of upper- and lower-case type. When listing persons’ names, identify them by roles (i.e., suspect, victim, witness). Conclusions should be articulated in detail. There are a variety of resources that provide details on constructing police reports. This should be used to supplement the process to improve reports.

Police Report Writing

Resources

Bulletproof Report Writing: A Field Guide for Police Officers, Anthony Bandiero.

Report Writing for Law Enforcement: A Hands-On Approach, Dick Blust

Grammar Saves Lives! Volume 1, Professional Writing for Law Enforcement Officers, Steven Starklight.

Grammar Saves Lives! Volume 2, Professional Writing for Law Enforcement Officers, Steven Starklight.

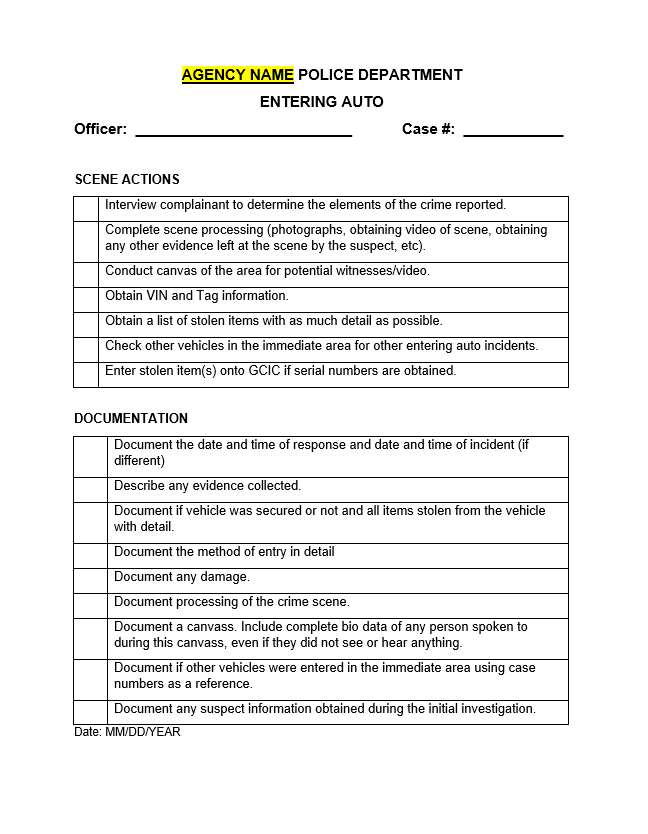

Checklists

Officers respond to multiple calls for service every day. Once on scene they meet with the victim/complainant, assess the scene, collect evidence, interview witnesses, determine what action is required, and possibly arrest a suspect. Afterwards, officers prepare a report that vividly and accurately describes all their observations, decisions, and actions. The task is made more difficult when officers respond to several calls before they can complete their report. When this occurs, they may not recall the details of events that occurred at each incident location.

One approach to ensure reports are prepared in a consistent manner across the department is to employ the use of checklists. Checklists have been effectively implemented in a variety of complex professions such as health care, aviation, construction, and computer coding. Each of these have resulted in enhanced performance, reduce mistakes, and improved operations.

"One approach to ensure reports are prepared in a consistent manner across the department is to employ the use of checklists. "

It is important to note, when agencies implement checklists, leaders should expect pushback from individuals who view them as a “simplistic, controlling, and a process that is beneath them.” This reaction has occurred in every profession that implemented the use of checklists. In time, however, individuals overcame their resistance.

When creating checklists, it is important engage prosecutors, investigators, and officers who have greater insight into what needs to be included in a report. The goal is not to check the boxes. Rather, checklists should be designed to serve as a reminder of the actions to be taken and recorded in the report. Officers must have the latitude to utilize their judgement at a scene of how to accomplish this as well as ensure observations and tasks are completed and thoroughly documented. As part of this process, it is just as important to identify tasks that were not accomplished (i.e., persons who were not interviewed or witnesses who were not located) as well as those who were.

When formatting the checklist, limit each to 5 – 9 items. Structure the statements into simple, practical reminders of the important steps to be taken without detail.

Reminders can be formatted using one of two formats:

Do – Confirm lists are likely to be more common for law enforcement agencies. Using this format, officers perform tasks based on memory, then stop and review their actions to ensure they have completed the required tasks.

Read – Do lists are structured like a recipe, that describe steps to be completed.

All the reminders should be placed on one page, using upper and lower-cased lettering, with simple and exact language common to law enforcement officers. The font should be in a sanserif type such as Helvetica.

Prior to distributing a checklist engage staff to field test the process. Once the checklist is implemented, it is important to continuously improve the processes by periodically reviewing and identifying issues and lessons learned. In time, individual officers, supervisors, and prosecutors will see enhanced outcomes and recognize their value. (Samples of checklists are available from the GACP website.)

Reviewing Body Worn Cameras When Writing Reports

Body worn cameras often capture the actions and statements of the witnesses, victims, suspects, and officers. This provides additional evidence needed to support the prosecution or clearance of an alleged suspect. At the same time, it is important to note, the officer’s body position may prevent the camera from capturing an officer’s observations. Conversely, the camera may record behaviors or statements the officer did not observe. There are a variety of legitimate reasons for an officer not observing behaviors captured by the recordings. For example, the officer may have been looking in another direction or their attention may be focused on other persons.

The officer’s report should be based upon their own observations. However, some studies suggest reviewing body worn camera footage increases officers’ memory and enables them to provide a more accurate account of the event.

If agencies permit officers to review their BWC recordings when preparing their reports, one study found when officers first write a report before reviewing their BWC recordings, their revised reports were more detailed and accurate.

Collaboration by Officers When Writing Reports

Some agencies may allow officers who respond to an incident location to collaborate with each other as they prepare their reports. While the practice has not been extensively studied, one found having two officers to work together to prepare an investigative narrative had less information than requiring they work separately. Also, when officers make notes immediately after responding to the calls they had less incorrect information.

Use of Artificial intelligence

Over the last decade the process of composing police report narratives has transitioned from handwriting and in some cases dictating, to use of word processing software. While technology has enabled officers to document more information faster, calls for service that require an incident report continue to be one of the most time-consuming function officers perform. One promising alternative for creating more detailed report narratives faster the use of artificial intelligence (AI).

There is a wide divergence of factors and opinions regarding AI that are outside the scope of this article. Some prosecutors have refused to accept police reports that have been created with open-source AI. Prior to investing in and implementing AI, it is important for agencies to work with prosecutors to review the various options and discuss concerns prior to moving forward with its implementation.

One viable approach to using AI for creating incident report narratives is AXON’s Draft One reporting software. This system utilizes the officer’s body camera recordings to produce investigative narratives. When the officer returns to their patrol car, the report is available for them to download and review. The system provides prompts for officers to clarify actions taken. However, it is imperative officers review and edit the narrative. As part of this review, officers may find information they did not observe or recall. In addition, officers may recall information the system cannot synthesize. For example, injuries, damaged property, behaviors (i.e. crying, standing in a bladed position, clinched fists). In other instances, the officer will have made observations that were not captured or articulated in the report. These actions must be included in the narrative with appropriate clarifying language.

When considering the cost of the service compared to the time saved and the improved quality of reports, the system easily pays for the monthly fee in the time saved.

While the technology is continuously improving, some are wary of its implementation. Despite this, the use of AI can be one of the most significant advances to rapidly creating high quality, detailed police report narratives.

Summary

“The goal of law enforcement reports is to chronical an event, capture the elements of an alleged crime, collection of evidence, interviews with complainants, witnesses, and suspects.” Throughout this series, the emphasis has been on the recognition that ‘the police report by far is the most important piece of evidence in every criminal case.’ “The information provided in police reports is paramount for the successful prosecution of criminal cases and the conviction of offenders.” To accomplish this, the series has focused on identifying shortcomings in reports that impact the ability to obtain a conviction. Once these are identified law enforcement and prosecutors must partner with each other to resolve these issues.

- Annelies Vredeveldt, Linda Kesteloo, and Peter J. Van Koppen, “Writing Alone or Together; Police Officers’ Collaborative Reports of an Incident”, Criminal Justice and Behavior, Vol. 45, No. 7, (July 2018), p.1089.

- Colleen Wade, ed., Handbook of Forensic Services, (Washington DD: Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2003) pp.162-163.

- Anthony Bandiero, Bulletproof Report Writing: A Field Guide for Police Officers, Blue to Gold Enforcement Training, LLC., Spokane Washington, (2021)

- Atul Gawande, The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right, Metropolitan Books, Henry Hold and Company, LLC, 2009, p.171

- Miller, L,. Toliver, J., and the Police Executive Research Forum (2014), Implementing a body-worn camera program. Recommendations and Lessons Learned. Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, https://www.justice.gov/iso/resources/472014912134715246869.pdf

- Annelies Vredevldt, Linda Kesteloo, and Lieke Hidebrandt, “To Watch or Not to Watch: When Reviewing Body-Worn Camera Footage Improves Police Reports”, Law and Human Behavior, (2021), Vol. 45, No.5, p.435

- Annelies Vredeveldt, Linda Kesteloo, and Peter J. Van Koppen, “Writing Alone or Together; Police Officers’ Collaborative Reports of an Incident”, pp. 1085-1086.

- Eric Chartrand and Eric-Alexandre Verret, “Beyond the Scene: The Importance of Time Consumed on Incident Report Task Components in Workload-Based Patrol Allocation and Deployment Assessments”, Police Journal: Theory, Practice, and Principles, (2023), p. 6, DOI:10.1177/0032258X231192009.

- Richard Segovia and David Vacchi, “Police Writing Proficiency: Saving Officers Time in the Long Run: Factors that Contribute to Writing Proficiency in Law Enforcement Reports”, Advance, January 2, 2020. DOI:10.31124/advance.114902.v1.

- Annelies Vredeveldt, Linda Kesteloo, and Peter J. Van Koppen, “Writing Alone or Together; Police Officers’ Collaborative Reports of an Incident”, Criminal Justice and Behavior, Vol. 45, No. 7, (July 2018), p.1089.

Daphne Tarver

Daphne Tarver is Chief of the Investigations Division of the Gwinnett Solicitor-General’s Office. With 28 years of law enforcement experience, Chief Tarver holds a criminal justice technical certificate from Miami Dade College and holds numerous advanced certifications as well as serves on multiple boards and task forces.

Donna Fraser

Donna Fraser is the Deputy Chief Investigator for the Dekalb County Solicitor General’s Office with 30 years of experience with the State of Georgia and South Carolina, specializing in internal affairs and criminal investigations. She holds a Bachelor of Arts in Criminal Justice from St. Leo University.

Tiffany Griffin

Tiffany Griffin is the Chief Investigator for the DeKalb County Solicitor General’s Office. She has 23 years of law enforcement experience and holds a Bachelor of Arts in Criminal Justice and a Minor in Psychology, specializing in Criminalistics and a Master of Business Administration from Clayton State University.